On December 22, 2017, President Trump signed H.R. 1, commonly referred to as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, into law.

On December 22, 2017, President Trump signed H.R. 1, commonly referred to as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, into law.

The legislation has been described by the national media as the most sweeping change to the federal Internal Revenue Code (IRC) since 1986. These extensive changes to federal tax law affect businesses and individuals and contain many provisions that also have broad implications for state income taxes.

Federal Business Tax Changes

Key changes to federal business taxes—many of which will affect state income tax laws—include the following:

Reductions

- Reduction of the corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%, effective January 1, 2018

- Reduction in the deductible portion of any dividend received from domestic corporations

Limitations

- Limitation of nonrecognition of gain from like-kind exchanges to exchanges involving real property, effective for exchanges completed after 2017

- Limitation of deductions for interest expense to 30% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization through the 2021 tax year

- Limitation of net operating loss (NOL) deduction to 80% of taxable income for NOLs arising in tax years beginning after 2017

Repeals and Eliminations

- Repeal of the domestic production activities deduction for years beginning after 2017

- Elimination of NOL carrybacks for most taxpayers for NOLs generated in years ending after 2017, though these losses are carried forward indefinitely

Miscellaneous

- Full expensing for new and used qualified property acquired and placed in service after September 27, 2017, and before 2023

- Immediate taxation of previously nonrepatriated foreign earnings at an effective rate of 15.5% for liquid assets and 8% for illiquid assets

- Allowance of a 100% dividend-received deduction on qualifying dividends paid by foreign corporations to < 10% US corporate shareholder

States’ Approaches to Adopting Federal Tax Law

Understanding how the federal tax changes described above will impact a taxpayer’s state income tax requires looking at states’ approaches to conforming to federal tax law—also known as conformity.

There are three distinct approaches: rolling, fixed date, and selective.

Rolling Conformity

Some states generally automatically adopt federal tax changes as they happen—this is known as rolling conformity. These states will likely follow the new federal provisions.

Some of these states have historically enacted laws that resulted in a decoupling from certain federal tax provisions. To the extent that a rolling-conformity state has previously decoupled from a provision changed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, there would be no impact on the state level for that specific provision.

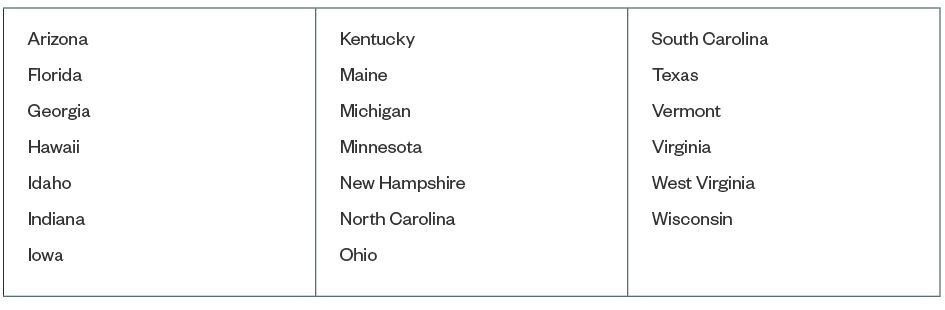

There are twenty-two states that take a rolling-conformity approach.

Rolling-Conformity States

All of these states impose their own corporate income tax rates, and therefore, none of them are impacted by the changes to federal corporate income tax rates.

Fixed-Date Conformity

The states that use the fixed-date-conformity approach will generally not automatically adopt federal tax changes—they will instead conform to the IRC as of a specific date. For these states to conform to the new federal tax law, their conformity date must be updated to a date after December 22, 2017.

There are twenty states that use a fixed-date conformity approach.

Fixed-Date-Conformity States

Taxpayers in these states will use the version of the IRC that existed as of the date that these states conform. As of the release of this insight, these states conform to a version of the IRC that doesn’t contain the new federal tax law. We expect that some of these states will update their conformity and incorporate some or all of the new federal law.

Selective Conformity

Five states—Arkansas, California, Michigan, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—adopt only selective provisions of the IRC, and generally do so as of a specific date.

California, for example, adopts only specific sections of the IRC and generally applies the version of the IRC that existed as of January 1, 2015, when doing so.

Impact on States’ Business Taxes

Corporate Tax Rate

One of the most publicized provisions in the new tax law is the reduction of federal corporate tax rates. Because states generally don’t conform to federal tax-rate changes, state taxes are expected to take on a greater importance for tax-paying businesses.

State taxes paid subsequent to the new law will likely represent a larger percentage of many taxpayers’ overall tax burdens.

Domestic Production Activities Deduction

The federal repeal of the domestic production activities deduction (DPAD)—also known as a Section 199 deduction—could produce interesting results in the states that conform to a version of the IRC that contains the DPAD. In these states, a state-only DPAD may still be available, even though the provision has been repealed for federal purposes.

Foreign Income

Many states have state-specific modifications that allow for a subtraction from federal taxable income for amounts treated as foreign income.

This means that even in rolling-conformity states that adopt the federal tax changes, there could be a state modification that allows for a subtraction of foreign earnings included in federal taxable income pursuant to new provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Impact on States’ Individual Taxes

The new tax law also contains a number of individual tax provisions, most notably:

- Reduction of individual tax rates

- Limitation on deductibility of mortgage interest

- Limitation on the deductibility of state taxes

- Creation of a 20% deduction for pass-through entity (PTE) income

Individual Tax Rates

Like the reduction to the corporate tax rate, reductions to individual tax rates won’t directly impact individuals’ state income tax computations because states don’t conform to federal tax rates.

State Income Tax

Similarly, the limitation on deductibility of state income tax doesn’t impact most individuals’ state income tax computations. This is because most states require deducted state income taxes to be added back to federal income while computing state taxable income.

PTE Income Deduction

Most states won’t adopt the new 20% deduction for PTE income, because the federal deduction is allowed as a deduction in computing taxable income, not as a deduction in computing adjusted gross income (AGI). Only the following six states use federal taxable income as the starting point in computing state taxable income:

- Colorado

- Idaho

- North Dakota

- Oregon

- South Carolina

- Vermont

Because these six states use federal taxable income to determine state taxes, their lawmakers will need to take action if they choose not to adopt this new federal deduction.

Next Steps

Major business and individual tax changes were enacted with the signing of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Taxpayers will need to understand the three principal ways in which states adopt federal tax laws—as well as the dates on which states plan to conform to federal law—to determine the impact the federal tax changes will have on their state tax liabilities.

We’re Here to Help

If you’d like to learn more about how the new tax laws will affect you, contact your Moss Adams professional. You can also visit our dedicated tax reform page to learn more.