A previous version of this article was published in the summer 2019 edition of Association of Health Care Internal Auditors’ New Perspectives.

.jpg) Lean health care, or lean for short, is an approach to managing health care operations that can help health care organizations reduce growing costs. Internal auditors are trained to see whether processes perform to specified levels of expectation or are even necessary. Lean health care can help improve internal audit functions and provide measurable value for health care organizations by focusing on eliminating waste to improve efficiency and lower cost. As shown in the figure below, health care in the United States isn’t only incredibly expensive, it’s also less effective, as measured by life expectancy, compared to other countries. Despite major advances in medicine, the outlook hasn’t changed much in 25 years when comparing accounts in the World Bank, World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health and Jeremy N. Smith’s 2015 book Epic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients.

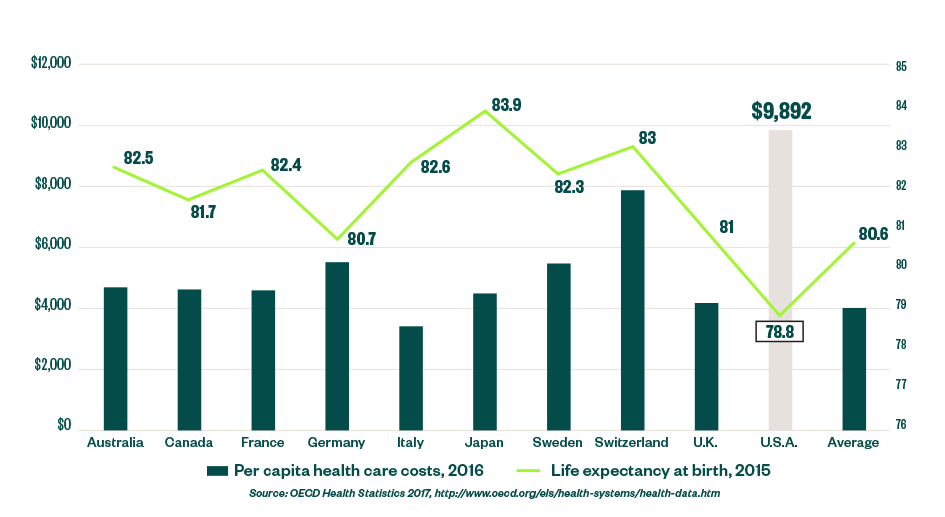

Lean health care, or lean for short, is an approach to managing health care operations that can help health care organizations reduce growing costs. Internal auditors are trained to see whether processes perform to specified levels of expectation or are even necessary. Lean health care can help improve internal audit functions and provide measurable value for health care organizations by focusing on eliminating waste to improve efficiency and lower cost. As shown in the figure below, health care in the United States isn’t only incredibly expensive, it’s also less effective, as measured by life expectancy, compared to other countries. Despite major advances in medicine, the outlook hasn’t changed much in 25 years when comparing accounts in the World Bank, World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health and Jeremy N. Smith’s 2015 book Epic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients.

The Relative Non-affordability of Health Care in the United States

Waste

Waste is quite prevalent in health care, and focusing on its elimination can be a major solution to cost problems. In an article published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Donald Berwick and Andrew Hackbarth state, “The opportunity is immense. In just six categories of waste—overtreatment, failures of care coordination, failures in execution of care processes, administrative complexity, pricing failures, and fraud and abuse—the sum of the lowest available estimates exceeds 20% of total health care expenditures.”

Waste Elimination

At the beginning of the 20th century, Henry Ford defined waste in business as the waste of time, but it can also be defined as anything that doesn’t add value to the product or service being delivered to the customer. In other words, there are only two states of being: adding value or not.

In Japan, Ford’s concepts became central features of the Toyota Production System, known today as lean manufacturing. While the concept of waste elimination can be applied to any industry, its application in health care has been notably successful. Prominent examples include the implementation at the Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle and Park Nicollet Health Services in Minneapolis as highlighted in John Black’s The Toyota Way to Healthcare Excellence: Increase Efficiency and Improve Quality with Lean. Clinicians, clinical professionals, non-clinical staff, and administrators—the operators of health care processes—either add value by changing the health of patients in a positive way, or they don’t.

Health Care Waste

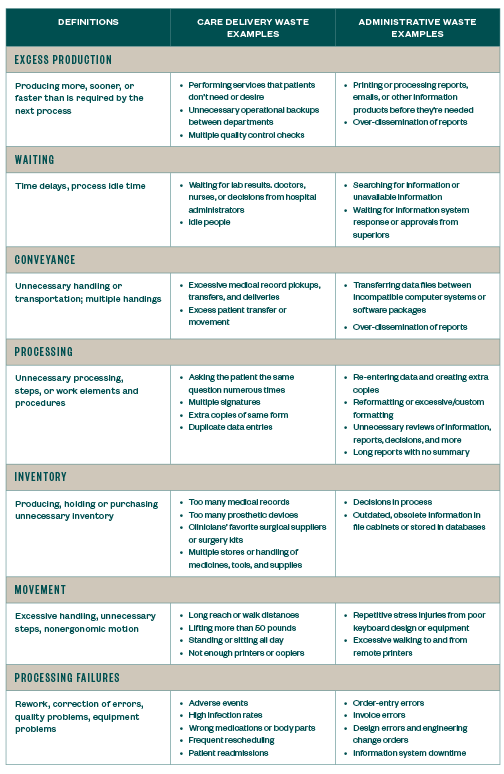

Ford identified seven types of waste in his processes. For health care, we generalize the types of waste as illustrated below.

Waste can be easily identified by performing time studies on the work carried out by health care professionals. Perhaps not surprisingly, it’s estimated that between 5% to 50% of time is wasted in health care, the same rate as 30 years ago when lean manufacturing made time studies popular again in manufacturing. The wasted time signals when health care operators aren’t performing tasks that change the health of patients. Instead, they’re performing the non-value-added examples identified under the seven types of wastes.

This underscores Berwick and Hackbarth’s estimate that 20% of health care expenditures are wasted, highlighting defects in the care process. It doesn’t necessarily include the six other non-value-added wastes that plague health care processes and institutions. The extra wastes are often gauged by personal experience, but can be measured almost as exactly.

The Practice of Going to Gemba

Health care internal auditors can observe these issues for themselves during the natural course of conducting internal audits. In Japanese, the practice of observing for oneself is called genchi gembutsu, often referred to in lean as “go to gemba.” Gemba is a Japanese term meaning the real or actual place, which, in the world of lean, equates to the workplace where clinicians, clinical professionals and clinical staff have direct contact with patients.

One area that lean advisors are somewhat suspicious is digital data, which is often input incorrectly and without correct time stamps, if entered at all. In the evolution of manufacturing, for example, the location and amount of inventories were often wrong after billions of dollars were spent to adopt manufacturing resource planning (MRP), which promised to bring inventories under complete control.

The only way to resolve the issue was to ignore the digital numbers and physically visit warehouses and interview fork lift drivers. Drivers put the materials on shelves, but not always the shelves indicated in digital data, and frequently behind other materials not recorded as stored in these locations.

Today, health care implementation of electronic health records seems to follow manufacturing’s poor example. The data in systems doesn’t correspond perfectly, or even closely, to reality. In health care, as well as manufacturing, lean experts insist clients go to gemba to learn the truth empirically, or at least confirm that data and controls in systems can be trusted.

Internal Audit Opportunities

Going to gemba is analogous to auditing. Over the course of one to five years, depending upon the size of the organization, internal auditors will physically and virtually visit practically every one of their organization’s processes. In their never-ending quest to assess the compliance of actual practices to standards or internal controls, auditors are like line inspectors focusing on time and quality.

Finding opportunities for improvement in the form of non-value-adding wastes is a similar exercise. The gaps in this instance are between the current state—filled with observable wastes—and an ideal future, waste-free state. Finding these gaps involves the analytical thought processes of an internal auditor and the very same risk areas already on the auditor’s schedule. All that’s required is a new viewpoint that factors in the seven wastes. Auditors need to look through the lean lens.

Taking Steps to Evaluate Waste in Processes and Operations

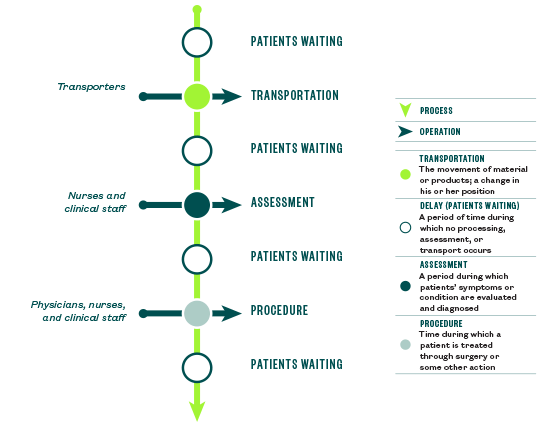

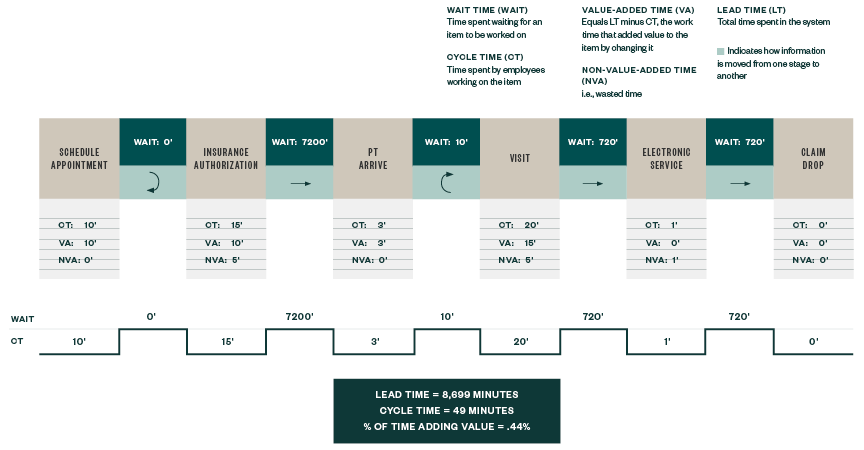

This new perspective of using a lean lens helps to approach the experience by differentiating the normal operations of health care from its processes as demonstrated in the figure below. Health care operations include the specific tasks performed by clinicians, clinical professionals, administrators, and others that are either value-added or non-value-added.

Health care processes involve multiple tasks and operations as experienced by patients as they’re inevitably handed off from one operation to another. This is rich ground for improvement. There’s evidence to suggest that at least 35% of sentinel events and almost 80% of all serious medical errors in US hospitals occur during handoffs, the spaces in between operations, not during the operations themselves. When determining how to start a gemba visit, internal audit can follow the patients as the best first step in identifying the most serious sources of waste in the process, as noted in Joint Commission’s Improving Handoff Communications: Meeting National Patient Safety Goal 2E research study.

Processes and Operations

Case Studies

When going to gemba, internal auditors can expect to find gaps that translate into improvement opportunities. Below are three examples.

A Major Urban Medical Center in the West

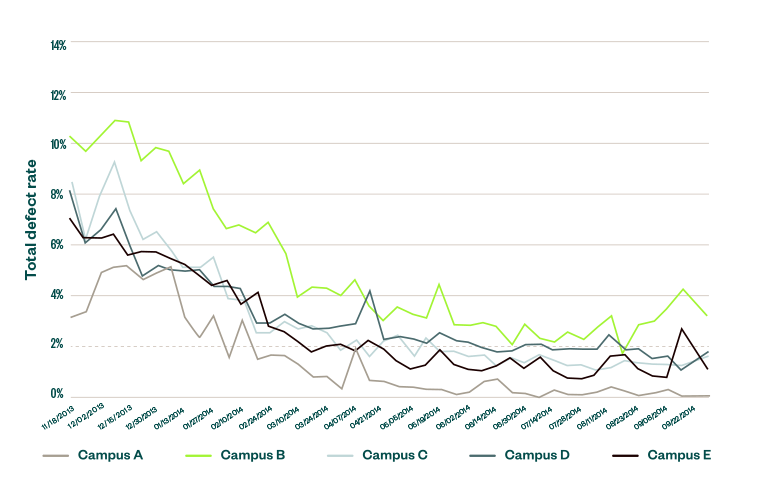

A team was tasked to help reduce barcode scanning defects that plagued a major urban medical center with five separate campuses.

Aside from the considerable risks to patient safety, time was wasted to both discover and fix the defects. Time is easy to measure, and was adopted as a target that could be used to measure improvement. Over the course of many months, the defects and the time spent fixing them were dramatically reduced. As shown below, defects were practically eliminated in the case of Campus A.

Patient Barcode Scanning Effects

A Small Clinic in Alaska

A small tribal health clinic that served several remote coastal villages in Alaska experienced serious trouble with its revenue cycle in 2005.

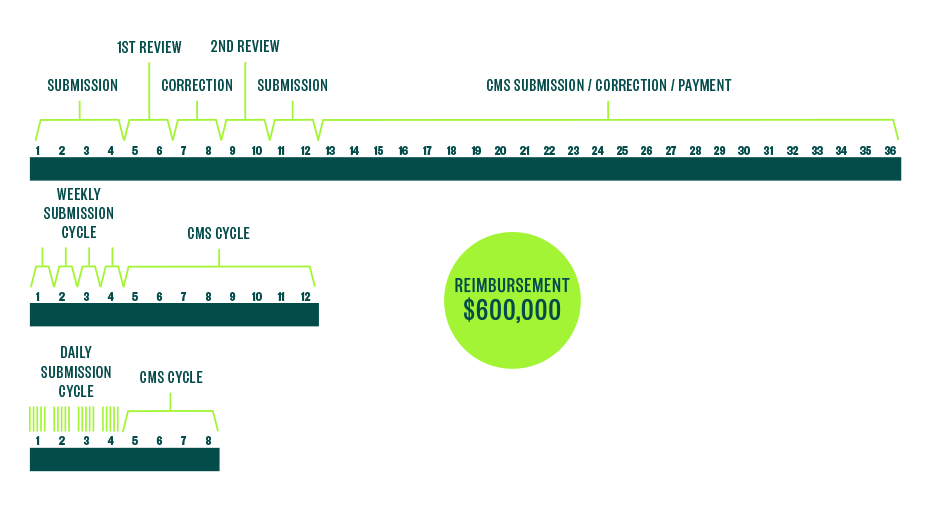

The clinic was staffed with certified public health aids (CPHAs). Once a month, the CPHAs faxed their patient encounter forms in large batches to the accounting office, which always discovered defects when processing them. The defects were then sent back to the CPHAs for correction. All defects weren’t always corrected, giving rise to another round of corrections. As a result, the clinic was often late in submitting claim forms to the regulatory agencies and other payers. The submissions themselves contained defects, resulting in still more rounds of corrections. The bad situation was only getting worse, and the clinic was short roughly $600,000 of reimbursements, threatening its very existence.

Revenue Cycle Improvement

To identify the cause of this problem, the clinic used sticky notes to map its revenue cycle process from beginning to end. Upon analysis, it discovered that the monthly practice of faxing patient encounter forms in large batches created a huge and artificial bottleneck in the accounting office.

If CPHAs submitted their patient encounter forms more frequently, the lead time to final submission of the claims could be shortened. Moreover, the accounting office would be able to find defects and fix them in a timelier manner, resulting in fewer defects submitted to payers.

At the end of workshop, a new system was immediately put in place. CPHAs began submitting their patient encounter forms weekly. This promised to reduce processing lead time and defect discovery time by a factor of four. In addition, the clinic committed to expediting the launch of reliable internet service to its remote communities. This permitted CPHAs to email their patient encounter forms and improve communication between the accounting office and the CPHAs. Once the internet service was in place, the CPHAs agreed to submit their patient encounter forms daily. This promised to reduce processing and defect discovery lead time by a factor of 30.

The mathematical relationship between throughput and time is governed by Little’s Law, which states that T = WIP/CT, or Throughput = (work in process)/(cycle time). Rearranging terms, we find that CT = WIP x T. By reducing the time interval between the submission of patient encounter forms, the clinic reduced its average work in process inventory of patient encounter forms on the controller’s desk. As you can see, the CT of the process is reduced in direct proportion to the amount of WIP or inventory in the process.

This led to quite the success story. When the revenue cycle was fixed, the clinic was saved, and so much non-value-added waste was discovered and eliminated that the clinic was even able to afford a full-time physician and open a dental office as well.

Large Midwestern Medical Center

The revenue cycle at a large Midwestern academic medical center was much more complicated. Going to the gemba and mapping the process in 2017 and 2018 revealed that there were separate process flows for all sorts of claims. In one case, there was so much waste in the process that lead time from service delivery to claim submission ranged from 9.5 to 14.4 days. A long-term goal was established so all future claims would follow a single path with a delivery of service to claim submission of only one day. A diagram of the future path of claim submission appears in the figure below. The savings from all expected reductions in claim submission lead times are forecasted to be almost $7 million per year.

Revenue Cycle Improvement

Lean Passes the GAAP Test

In almost all cases, the remedies associated with lean methods involve a combination of standardized work, visual work instructions, and embedded controls such as checklists and automated mistake-proofing. Work standards are based on best clinical practice and complicit with all government regulations and company policies. Embedded controls reduce the risk of non-detection. Lean methodologies through standardized work and embedded controls are in line with the four tenets of GAAP: materiality, conservatism, consistency, and matching, according to Jean Cunningham and Orest J. Fiume’s Real Numbers: Management Accounting in a Lean Organization.

Next Steps

If your organization already has lean experts or departments devoted to lean or lean six sigma improvement, a variant of lean that combines elements of total quality management with Toyota’s just-in-time production, ask them to take you on a gemba walk. You may even want to request to become a team member or participate in a five-day kaizen workshop. Kaizen is Japanese for continuous improvement. These workshops teach how time processes and uncovers waste streams, as well as how to redesign a health care process.

With the rise of blockchain, data analytics, and artificial intelligence, all professions are contemplating their future. Routine processes as complicated as legal research, medical diagnosis, and auditing are now significantly aided by computers, and some may be automated in the future. Some experts even believe that physical auditing may become obsolete because blockchain creates a near-perfect record of every transaction.

That may not be the case yet, but professions are challenged to reimagine how they can add value to their clients. There are many reasons to believe that auditing will survive. Blockchain itself will still need auditing, and beyond that, the process of auditing, especially the process of going to gemba, can’t be replaced entirely by remote sensors and computers. Besides the advantage of simply being in the real place, remote sensors may not be good at prioritizing opportunities.

We’re Here to Help

With a renewed focus on the seven wastes, auditors can bring a new, critical perspective on what they see and provide solutions for their clients. To learn more about how lean health care can help your organization, contact your Moss Adams professional.