This article is part of a three-part series on the cost of goods sold—a key metric that can help wineries understand their profit margins. In our previous article we provided an overview of how to calculate it and why it matters. Here, we’ll dive into steps for setting up a system and practices to derive this metrics. In our final article of the series, we provide cost of goods sold insights specific to wineries of different sizes.

To understand your winery operation’s performance and gauge its profitability, you must know how much it costs to produce your wines. Two measures provide that insight: your winery’s cost of goods produced (COGP), also known as wine in process (WIP), and the cost of goods sold (COGS). The COGS is the COGP of the specific wines sold in a given period.

Since the winemaking process typically takes two-to-four years to transform grapes into a finished bottle of wine that is ready for sale, it’s important to track the cumulative cost of producing that wine–its COGP–from start to finish. That production cost, which includes raw material inputs, direct labor, production supplies, and related overhead costs is recognized on the balance sheet as an addition to the cost of wine inventory. Eventually, when the finished wine is sold, the costs incurred with making that product—the COGP—are recorded on the income statement as the COGS for the period. At the same time, a matching offsetting entry is made to reduce the inventory value on the balance sheet.

Understanding the COGS for your business can potentially help you run a more efficient and profitable company. Calculating the COGS helps you track direct and indirect costs throughout the entire winemaking process. The process for setting up a COGS system, regardless of your winery’s size, includes seven main steps.

1. Identify Personnel and Users

The first step is to identify the personnel—internal and, if needed, external—who know how to and will be able to account for COGP and COGS in accordance with the industry standard, accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America (U.S. GAAP).

Management should also consider who will be using the financial statements. Besides the management team, users of the financial statements might also include a board of directors or board of advisors, investors, lenders, vendors, and potential investors or acquirers.

2. Review Reporting Requirements

In the wine industry, a suggested best practice in accounting for COGS is to follow U.S. GAAP. This is particularly true for larger wineries, which often must adhere to U.S. GAAP for financial reporting requirements of certain financial statement users. Smaller wineries may be able to modify reporting as needed to accommodate resource and budget constraints as well as any system limitations.

It’s also essential to understand the needs and reporting requirements of the users identified in Step 1. Any of these users could ask for financial statements on a U.S. GAAP basis and may even request a report from an independent CPA to provide various levels of assurance as to the company’s compliance with U.S. GAAP.

3. Set up the Ledger to Categorize Costs

Once you have an understanding of reporting requirements, it’s important to set up the general ledger to track costs in the proper categories and at the appropriate level of detail or unit of account. This allows for easier extraction of costs to be analyzed and assigned or allocated within the inventory costing process. Typically, wineries will record production costs within the crush and ferment, cellar, and bottling cost centers and categorize them by the following type of expenditure:

- Materials

- Labor

- Overhead

For a more in-depth explanation of these categories, see our article in the series, Accounting for the Cost of Making and Selling Wine.

4. Create Processes for Capturing and Reporting Expenditures

The next step is to create internal reporting protocols to appropriately record COGP and develop a process and rationale for costs to be assigned to specific lots or blends and allocated between departments. It’s ideal to establish departments that correspond to the natural flow of the winemaking process.

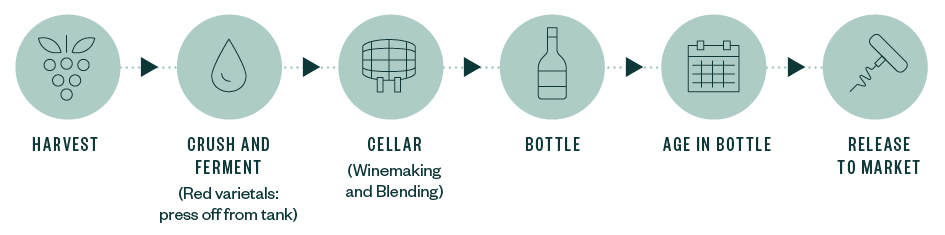

The major steps or phases in the winemaking process are:

While not a specific phase in the winemaking process, the cost of operating and running your facility is an important consideration. These costs can be captured in a facilities department cost center. Those costs can then be allocated to the above stages of the winemaking process. If the facility or facilities are shared by the winemaking and other departmental functions such as administration, sales and marketing, or hospitality, then the facilities costs should be allocated to wine production and the other functions.

Internal Protocols

Incorrect input costs can skew the final product cost calculations and produce an inaccurate and misleading profit margin, so part of good internal reporting protocol is having a system for providing accurate information relating to inventory flow and quantities. Ongoing communication between the winemaking staff and accounting staff is critical to establishing accurate inventory values and COGS calculations.

Besides maintaining good communication between the production and accounting teams, staff can take the following steps to help promote accuracy:

- Verify and record the quantity and condition of grapes and packaging supplies as well as the wine volumes upon completing winemaking activities like pressing, racking, topping, blending, and bottling.

- Establishing normal production volumes is also important to establish appropriate overhead rate allocations and identifying when variances from the baseline occur.

- Keep detailed notes of activities and record changes in harvest yields and wine volume, so that relevant adjustments can be made to the inventory values.

- Record and communicate the actual final production counts by label.

5. Develop Costing Protocols

Next, develop detailed and thorough costing protocols for different varietals, blends, and labels. Not all wines are made the same way—some require months to make, others years to make; some wines spend time in oak barrels, others don’t.

Create costing protocols with input from winemakers, production staff, and other department heads to help ensure the costs accurately reflect the level of inputs and effort required to make different wines. Often it’s best for inventory cost accounting personnel to routinely observe the winemaking process, inquire about existing processes, and be alert to changes to the process that necessitate changes in the accounting costing approach or data gathering.

In planning and setting up your tracking and costing system, it’s important to consider the wine manufacturing product cycle.

A good costing system will include a worksheet or process that is tailored to and mirrors the production cycle, starting with the raw materials and adding in the other components, such as labor, services, and overhead, along the way.

An organized system, maintained from start to finish, can provide the winery operator accurate account balances throughout the wine production process. This includes accounts that detail balance sheet assets including bulk and cased wine inventory values, capitalized expenses, and eventually, the revenue and COGS.

Contra-Accounts

In addition to establishing the protocols outlined above, it’s helpful to set up contra-accounts in your general ledger. Contra-accounts are used in a general ledger to offset or reduce the value of a related account when the two are netted together. A contra-account's natural balance is the opposite of the associated account. If a debit is the natural balance recorded in the related account, the contra-account records a credit.

Contra-accounts are useful because they enable users to preserve the historical value in a main account, while offsetting that historic value in full or in part for a particular reason. For example, a reason might be to show the net difference—also known as book value—or to allocate costs from a production cost center to wine inventory on the balance sheet.

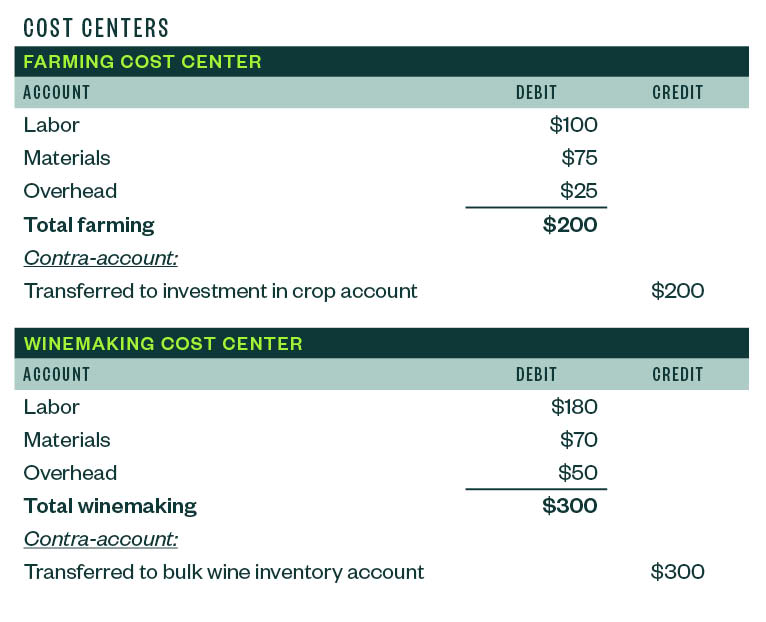

Here’s how to set up and use contra-accounts.

Establish Contra-Account Within Production Cost Centers

You’ll typically want to establish contra-accounts within these production cost centers:

- Farming

- Wine Production, including crush and fermentation, as well as cellar and aging

- Bottling

Allocate Production Costs

Each cost center will have direct costs, direct labor, and overhead costs. Overhead should include an allocation of facilities costs. See Accounting for the Cost of Making and Selling Wine for details on how facilities costs can be allocated.

Taking time up-front to define how certain overhead items will be allocated can offer more consistent results year-to-year and build confidence in the information provided by the system, while reducing confusion and wasted time.

How to Use Contra-Accounts

Typically, a contra-account will be used to transfer portions or totals of each cost center or department to inventory on the balance sheet. If, however, a winery is providing custom winemaking services to clients, a portion of the winemaking costs will be allocated from each cost center to the costs of custom winemaking services on the income statement. Whoever manages the accounting for the winery should have knowledge of how this is done within the company’s accounting software.

Using contra-accounts enables you to retain the expenditures detail within each cost center while showing the increased investment in your wine inventory on your balance sheet. To accomplish this, create adjusting entries that: 1) credit the contra-account by the total of the cost center expenditures for the period, and 2) debit the balance sheet wine inventory account for that same amount.

Example

Here’s an example of how to set up and utilize a contra-account.

For each period, enter the labor, materials and overhead costs into their respective accounts and cost centers. These account entries will be recorded as "debits" and the cash or accounts payable account will be credited. Then at the end of the period, the appropriate costs are transferred to inventory by crediting the contra-account and then debiting inventory in the amount of costs incurred during the period. Finally, inventory is then adjusted at period-end based on physical inventory remaining on hand.

Review Contra-Accounts

Periodically, these groupings should be revisited to verify that new accounts are properly grouped and existing accounts are being utilized as originally intended. From a management perspective, winery operators should break down the accounts comprising COGP to a level of detail that allows for effective management of operations, while keeping financial statements at a summary level.

Review for Indicators of Impairment

A critical step in U.S. GAAP to not overlook is the assessment of inventory for impairment that would require a reduction in the inventory amount on the balance sheet through a charge to the income statement in the reporting period in which such impairment has occurred. A reduction in inventory value may result from partial damage, physical deterioration, or changes in market prices. The specific approach to determining the amount by which to write-down inventory in such circumstances depends in part on the specific U.S. GAAP inventory method used; however, under every method the adjusted carrying value of the inventory becomes its new cost basis and the inventory is not adjusted back up, even if the conditions that initially caused the write-down are no longer present.

6. Perform Inventory Counts

Even with accurate cost of production information, winery operators must have a thorough record of the inventory quantities on hand at each stage of production in order to properly apply costs. Therefore, one of the most critical processes for a winery to have in place is an effective inventory count system. This includes both manual counting as well as automated perpetual inventory tracking systems.

A physical count is typically performed monthly or quarterly and should coincide with the end of each reporting period. Occasionally, certain regulatory or contractual requirements may dictate that inventory counts be performed more often than once per reporting period. Tasting rooms often count their wine inventory and usage daily. At a minimum, wineries should perform a complete physical inventory count at the end of each fiscal year.

Inventory Physical Count Strategies

While the inventory tracking process can be time-consuming, there are steps you can take to help improve the efficiency and accuracy of your physical inventory count process and the resulting records. These include the following:

- Implement well-defined inventory count procedures that are documented and communicated with the count team.

- Assign multiple employees to independently double-check and supervise the count

- Consider performing “blind counts,” meaning the people doing the count won’t have access to reported quantities of inventory and, therefore, won’t be biased by knowing what the records indicate should be present.

- Involve multiple departments, such as accounting, production, and sales.

- Consider suspending production activities and wine shipping activities while the inventory count is underway because moving inventory is more difficult to count and increases the potential for mistakes.

- If needed, plan and coordinate the timing of any suspension with production, sales, and accounting departments.

- Assign one person or department to reconcile differences and determine when the physical inventory count is completed so production activities can resume.

- Provide streamlined inventory count sheets that enable multiple locations to be tracked for the same inventory item.

- Report final inventories with common units, such as nine-liter equivalent cases, so calculations and formulas can be applied uniformly to reduce errors in workbooks.

Inventory Accounting Processes

It’s important to keep an up-to-date record of the inventory available. This can be accomplished with one of the two inventory accounting approaches:

- Periodic inventory

- Perpetual inventory

Periodic Inventory Approach

With a periodic inventory approach, COGS isn’t recorded until a count is done and ending inventory is adjusted. There is no continuous record taken to determine the inventory value or quantities. This approach involves recording costs to the expense accounts during a given period and transferring them to inventory on the balance sheet at each reporting period end and then adjusting based on the physical inventory on-hand. This is typically done on a monthly or quarterly basis. As wine is bottled, winery operators will usually estimate the cost of the blends used in the bottling, and transfer those costs, along with estimated bottling costs, to bottled inventory, and calculate a preliminary cost-per-case of wine.

The primary benefit is that the inventory tracking and costing method is cheaper than the alternatives. The downside is that it involves manual steps, which increases the potential for error, and the inventory count becomes outdated the moment a sales or production transaction occurs. Also, estimated costs may not be accurate and can skew the final numbers. This approach also results in lack of accurate and timely financial reporting results in between each physical count and adjustment process.

Perpetual Inventory Approach

Perpetual inventory systems are an alternative to periodic systems. They utilize enterprise resource planning (ERP) or other computer software to track inventory transactions as they occur. This means inventory volumes and values are automatically adjusted every time there is a sales or production transaction affecting inventory.

A perpetual inventory system requires a fairly powerful software system that’s updated on a transaction level to accurately provide operational data for all areas of the winemaking operation. These systems eliminate the need for the manual spreadsheets of the periodic inventory system and integrate all inventory activity that also usually includes recording entries in the general ledger accounting system of the business. Transactions are recorded on an item-level basis, and as they’re completed, the system calculates the financial impact and inventory quantity impact of the transactions.

Many owners find that having real-time perpetual inventory quantity and financial data invaluable—especially in the middle of a busy wine release when sale orders are high.

While perpetual inventory systems can be expensive and time consuming to select and implement, technological advances have made such software more affordable for small and mid-size companies and enabled them to operate more efficiently by reducing the time and effort required to manually track their inventory.

Hybrid Systems

Many smaller wineries utilize a combination of these systems, with a perpetual system used to track finished goods inventory—relieving inventory when shipments are processed—and a periodic system for tracking and costing bulk wine inventory.

7. Consider a Point-of-Sale System

Wineries with onsite retail operations, such as tasting rooms or wine clubs and e-commerce, often benefit from implementing a point-of-sale (POS) system. Due to their expense, POS systems were once largely only found in restaurant operations and large retailers. However, technology advances have made POS and credit card processing affordable, even for small winery operations.

Benefits

Large and small wineries that conduct retails sales—particularly cash sales—can leverage a POS to reduce the complexity associated with accounting for these transactions.

POS System Capabilities

- Track sales on an item-level, which is useful in sales and inventory analysis

- Track payment types and perform analyses of credit policies

- Reconcile payment types, which allows for better accounting and bookkeeping information

Additionally, a POS system reduces the risk of theft from within the retail operation. Cash is one of the most accessible areas for employee theft in a small business. Because the POS system tracks the amount of cash collected in the tasting room, daily reports can verify that the correct amount of cash was deposited into the bank.

Also, the wine itself may be a temptation to some employees or customers, and foregone revenue due to theft or excessive sampling can aggregate to significant amounts. A POS that closely tracks inventory or can compare sales to depleted inventory tracked elsewhere can enable owners to closely monitor and manage wine inventory as well as potentially reduce losses.

We’re Here to Help

For more information on how to set up a COGS system for your winery, contact your Moss Adams professional.

For additional insights on setting up and understanding the cost of goods sold for wineries, view the other articles in this series:

Accounting for the Cost of Making and Selling Wine

Understanding Your Costs: Tips for Wineries of All Sizes

Special thanks to Andrue Ott, Outsourced Financial Accounting Specialist, for his contributions to this article.