As private foundations turn to alternative investments to diversify portfolios and potentially increase their value, their leaders should know about the tax, fiduciary, and regulatory implications of making such investments.

The section below answers key questions regarding alternative investments that private foundation board members, executive directors, and other leaders should consider.

What Are Alternative Investments?

Broadly, alternative investments are those investments outside the traditional markets for stocks, bonds, and cash, including:

- Private equity

- Hedge funds

- Real estate

- Venture capital

- Private debt

- Commodities

Note that alternative investments can include holdings like art, antiques, and cybercurrency.

What Are the Benefits of Alternative Investments?

As with any investment, alternative investments provide advantages and risks for investors.

One advantage is that generally alternative investments have a low correlation to traditional investments, meaning that they often move counter to the stock and bond markets. Because of this, alternative investments can provide private foundations with a more diverse portfolio.

Other advantages include:

- Exposure to a broader range of investments. Alternative investments can provide private foundations with access to distinct, more sophisticated markets, like start-up companies, which could have high returns over the long run.

- Hedge against inflation. Investments in hard assets, such as gold or other metals and real estate can act as a protection against inflation.

- The potential for high returns.

What Are the Risks of Alternative Investments?

Alternative investments are often illiquid—making them more difficult to sell quickly than traditional investments. And alternative investments may require their investors to lock into the investment for several years.

Other disadvantages include:

- Alternative investments are difficult to value. Generally, they are nonpublic investments, making it hard to track market price.

- Most alternative investments aren’t regulated by the SEC.

- There are fewer benchmarks to make comparisons. It’s easy to compare the performance of a traditional investment to the S&P 500, or some other index. But benchmarks for alternatives aren’t as precise because of valuation issues.

- Alternatives generally come with higher fees.

For private foundations, an additional disadvantage may be the tax consequences associated with such investments. Alternative investments could impact a private foundation’s excise tax on net investment income and its unrelated business taxable income, and may also require additional state and foreign filings and reporting.

What Are the Tax Impacts of Alternative Investments?

Some of the more typical alternative investments can be organized as a partnership, a corporation, or a trust—although most commonly, they’re organized as partnerships or limited liability companies with income passing through to investors.

If organized as a partnership, S corporation, or trust, the alternative investments would generate a Schedule K-1, which reports the private foundation partner’s share of income, expenses, and other items.

If the alternative investment is organized as a C corporation, a K-1 isn’t issued, and the private foundation will need to determine if it’s required to pick up its share of the investment’s taxable income.

Other questions that private foundations should consider include:

- How and when will the foundation be notified of its share of income?

- Is the investment foreign or domestic?

Excise Tax

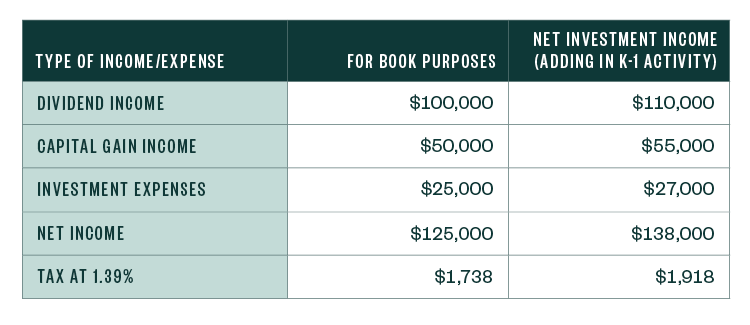

Most private foundations are subject to a 1.39% excise tax on their net investment income. Activity—both income and expenses or deductions—from alternative investments would be included in a private foundation’s calculation of net investment income.

If the activity from an alternative investment isn’t booked to a private foundation’s financial statements, that activity will need to be added when the private foundation calculates its net investment income.

For example, a private foundation included in its financial statements the following activity from its traditional investments:

- Dividend income of $100,000

- Capital gain income from the sale of investments of $50,000

- Investment-related expense of $25,000

In addition, the private foundation has an alternative investment whose K-1 shows $10,000 in dividend income, $5,000 in long-term capital gains, and investment expenses of $2,000. That activity would be added to the book income to calculate the total net investment income.

From this example, the K-1 activity added a net of $13,000 to the net investment income calculation, increasing the excise tax calculation by $18.

Unrelated Business Taxable Income

Alternative investments can generate unrelated business taxable income (UBTI) in two ways. The first is through debt-financing, either by the investment, or by the private foundation.

Generally, passive income from an interest in a partnership, such as interest, dividends, royalties, rents, and gains from the sale of securities are excluded as UBTI. But when an investment fund incurs debt to purchase investment assets, the income generated by those debt-financed assets, including passive income, are UBTI.

In addition, the private foundation may take out a loan to purchase the alternative investment, and then all the income from the investment is UBTI, regardless of the type of income.

The second way that alternative investments generate UBTI occurs when the investment operates a for-profit business. This income is generally UBTI even if the private foundation doesn’t directly participate in the for-profit business. While both are common within alternative investments, debt financing that causes UBTI happens more often.

Analyzing Schedule K-1

It’s important for private foundations to review the Schedule K-1 to determine whether the alternative investment generates UBTI, particularly the following areas:

- Line J, Partner’s share of profit, loss, and capital. Information here may determine whether the alternative investment’s activity can be aggregated for UBTI purposes, or whether the private foundation has an excess business holding.

- Line K, Partner’s share of liabilities. Information here may determine whether the alternative investment has debt financing.

- Box 1 – Ordinary business income (loss). Amounts in this box represent the private foundation’s share of income from some type of for-profit business operated by the alternative investment.

- Box 11 – Other income (loss). Amounts reported here may also be UBTI.

- Box 13 – Other deductions. Amounts reported here may be used as deductions against income reported in Boxes 1 and 11.

- Box 20V – Unrelated Business Taxable Income. This box represents the amount of taxable UBTI for the private foundation.

- Footnotes to the K-1. Information for Box 20V may be broken down in more detail in a footnote. In addition, K-1’s may have footnotes related to state-specific UBTI and foreign activity and foreign filings.

For most alternative investments, unrelated business taxable income will be reported in Box 20, Code V on the Schedule K-1, with additional information provided in a Box 20, Code V footnote.

As an example, the Box 20, Code V line may show UBTI of $20,000. It could also be broken down in a footnote as follows:

STATEMENT REGARDING UNRELATED BUSINESS TAXABLE INCOME FOR TAX-EXEMPT PARTNERS

Box 1: Ordinary Business Income $15,000

Box 6A: Ordinary Dividends $10,000

Box 13: Other Deductions $5,000

In total, this footnote also shows UBTI of $20,000. UBTI is reported on Form 990-T, and filed separately from the private foundation’s Form 990-PF. For tax-exempt corporations, UBTI on Form 990-T is taxed at the corporate tax rate, which is 21% in late 2021. At this rate, the UBTI of $20,000 in the example would generate tax of $4,200. For foundations set up as trusts, UBTI would be taxed at trust tax rates, which are graduated and top out at 37%, as of late 2021.

Occasionally, partnerships may not show an amount in Box 20, Code V, but still show an amount in Box 1, Ordinary Business Income, which represents the share of income generated from a for-profit business.

In these instances, the amount in Box 1 as well as any deductions in Box 13 related to the for-profit activity generally would make up the UBTI on the Schedule K-1 as the for-profit business likely is not related to the charitable mission of the foundation.

If the alternative investment is organized for tax purposes as an S corporation, the private foundation will also receive a Schedule K-1 similar to partnerships.

Unlike with partnerships, where passive income wouldn’t be UBTI unless there’s debt financing, all activity reported on the Schedule K-1 for an S corporation is UBTI to the private foundation. For this reason, it’s rarely recommended that private foundations invest in S corporations.

UBTI Silos

As part of the tax-reform act enacted in December 2017, exempt organizations that have more than one unrelated business activity are required to compute their UBTI separately by activity, also known as siloing. Previously, exempt organizations could aggregate unrelated trades or business, allowing losses from one activity to offset income from another activity.

Under the final regulations for this new law, investment activities can be aggregated as one UBTI activity if they’re:

- Qualifying partnership interests (QPI)

- Qualifying S corporation interests

- Debt-financed properties

A QPI occurs when an exempt organization holds a direct interest in a partnership that meets either the de minimis test or the participation test. Under the de minimis test, an organization can hold no more than 2% of the profit interest or 2% of the capital interest in a partnership.

Under the participation test, a partnership is a QPI if the organization holds no more than 20% of the capital interest and doesn’t significantly participate in the partnership.

For additional information on aggregating investment activities for UBTI reporting purposes including how to determine significant participation, please see our article, IRS Regulations on Unrelated Business Taxable Income Siloing.

An organization determines its percentage interest for both tests by taking the average of the beginning of the year interest and the end of the year interest, as shown in Line J on Schedule K-1.

An S corporation holding may be aggregated with other investment activities if the ownership interest meets the same de minimis test or participation test as a QPI.

State Reporting Requirements

When an alternative investment has UBTI, information on state UBTI is often included in the footnotes of Schedule K-1. A private foundation may not have a presence in a state, but a holding in an alternative investment may create a corporate or trust income tax filing obligation in states with UBTI.

In addition, sometimes the alternative investment will pay withholding tax to a state, and this information is also listed in the K-1 footnotes.

Some states don’t have an equivalent of the Form 990-T. In these cases, the private foundation would file a state corporate or trust tax return.

Foreign Reporting Requirements

An alternative investment may itself be a foreign entity, or it may invest in other foreign entities. In either case, foreign reporting requirements may be triggered depending on the ownership percentage in the investment or on direct and indirect transfers of cash or other property to a foreign entity. Penalties for failing to file foreign forms are significant.

The following are among the more common foreign forms.

Form 926, Return by a US Transferor of Property to a Foreign Corporation

This form is required to report transfers of cash or property to a foreign corporation—either when the organization owns at least 10% of the foreign corporation or when the amount transferred is more than $100,000 during the 12-month period ending on the date of the transfer.

In addition to a foundation making a direct investment in a foreign corporation, a foundation may also have to file the form if a partnership it owns makes such a transfer. The penalty for failing to file a Form 926 is 10% of the amount transferred, capped at $100,000, unless the failure to comply is because of intentional disregard.

Form 5471, Information Return of US Persons with Respect to Certain Foreign Corporations.

This form is required when the US investor owns 10% or more of a foreign corporation. Penalties for failure to file range from $10,000 to $50,000.

Form 8865, Return of US Person with Respect to Certain Foreign Partnerships

This form is required when a US investor contributes more than $100,000 to a foreign partnership in the 12-month period ending on the date of the transfer.

The form is also required if the US investor owns 10% or more of the partnership.

If an alternative investment makes a transfer to another foreign partnership and files Form 8865, then its partners won’t have to report the transfer. Penalties range from $10,000 to $100,000 for failure to file, with additional penalties if the failure to file is because of intentional disregard.

FinCEN Form 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR)

This form is for US taxpayers who have offshore accounts —foreign bank accounts, brokerage accounts, and mutual funds.

Individuals who have signature authority over the accounts also have a filing obligation. The penalty for failure to file can be as high as 50% of the value of the account.

What Are Audit Implications of Alternative Investments?

When private foundations invest in alternative investments, their managers also need to ensure that their financial statements properly reflect those holdings. The existence and the valuation of an alternative investment is the responsibility of the private foundation’s management.

With respect to existence, the auditors will be required to determine that the investments exist at the financial statement date and that the related transactions have occurred during the period. With respect to valuation, the auditor will need to determine if the investments are accurately stated at fair value. This is often more complicated as alternative investments are not publicly traded on an active market.

Because management is responsible for these aspects, management must have proper controls in place and an adequate understanding of the investments the foundation is making. A foundation can develop this understanding by performing due diligence on the investment before purchasing it; monitoring the investment continuously; and having financial reporting controls related to the accounting and reporting of the investment.

For the auditors, they will need to evaluate the adequacy of the foundation process to support the valuation and existence of the alternative investments. The auditors will also have to evaluate the quantity and quality of the audit evidence available. The auditors’ risk assessment should consider factors such as:

- Materiality of the alternative investments

- Nature and extent of management’s process and controls related to alternative investments

- Degree of transparency available to management to support its valuation process

- Complexity and liquidity of the alternative investments

What Are Regulatory Impacts of Alternative Investments?

Private foundations are subject to an array of rules and regulations intended to ensure that their funds benefit the public. In making alternative investments, private foundations need to know the regulations that govern excess business holdings and jeopardize investments.

Excess Business Holdings

The excess business holdings limit the ownership percentage a private foundation may have.

Business enterprises may include corporations, partnerships, trusts, and their holdings. The limitations are calculated using the following ownership definitions:

- Voting and nonvoting stock for corporations

- Profits and capital interests for partnerships

- Beneficial interest for trusts

In general, a private foundation may hold 20% of the voting stock in a corporation, while also considering the percentage of voting stock owned by all disqualified persons.

For example, if a private foundation held a 15% interest in a corporation while two disqualified persons owned 5% each, total ownership would be 25%, and the investment would be considered an excess business holding.

A disqualified person is one of the following:

- Substantial contributor to the foundation

- Foundation manager, such as officer, director, or trustee

- Owner of more than 20% of a corporation, partnership, or trust that’s a substantial contributor to the foundation

- Family member of an individual described above

- Corporation, partnership, trust, or estate in which any individuals described above own more than 35%

- Controlled or related private foundation that’s effectively controlled by the same person or that received substantially all of its contributions from persons listed in the first three points above

- Certain government officials

There are two additional thresholds for excess business holdings. If a third party has effective control of a business enterprise, then the private foundation and its disqualified persons may own up to a 35% interest in the business enterprise.

Finally, a private foundation doesn’t have an excess business holding in a business enterprise in which it, along with related foundations, owns 2% or less of the voting stock and 2% or less of the value of all shares outstanding.

The rules for excess business holdings exclude certain business enterprises. An investment in a trade or business that derives at least 95% of its gross income from passive sources isn’t considered a business enterprise.

In addition, any business related to the exempt purpose of the foundation isn’t considered a business enterprise, and neither is a program-related investment.

If a private foundation determines that it has an excess business holding, it generally has 90 days to dispose of the holding. If a gift or bequest tipped the private foundation’s investment over the threshold, the organization would have five years to dispose of the excess business holding.

An initial excise tax of 10% is imposed on the excess business holdings. A second 200% tax is imposed if the excess business holdings aren’t disposed of during the taxable period.

Private foundations should develop procedures to identify all disqualified persons and any potential excess business holdings. One approach could be to provide a list of the foundation’s investments and its level of ownership to disqualified persons, requesting acknowledgment of the percentage owned in the same investments by each disqualified person.

Potential ownership issues should also be vetted before purchasing an investment.

Jeopardizing Investments

Private foundations also face rules to deter them from making investments that might jeopardize their ability to carry out their exempt purpose.

An investment is considered a jeopardizing investment, according to the regulations, “if it is determined that the foundation managers, in making such investment, have failed to exercise ordinary business care and prudence, under the facts and circumstances prevailing at the time of making the investment, in providing for the long- and short-term financial needs of the foundation to carry out its exempt purposes.”

In exercising the requisite care, foundation managers may consider expected returns—for both income and capital appreciation—as well as the risks of rising or falling prices and the need to diversify the foundation’s investment portfolio.

They can determine if an investment is jeopardizing on an investment-by-investment basis and consider the portfolio as a whole at the time of the investment, not in hindsight.

The regulations don’t outright ban any type of investment but do provide examples of the types of investments that will be closely scrutinized. Those types of investments are:

- Trading in securities on margin

- Trading in commodities futures

- Investing in working interests in oil and gas wells

- Purchasing puts, calls, straddles, or warrants

- Selling short

The rules regarding jeopardizing investments don’t apply if the investment has been gifted to the foundation, as long as the foundation didn’t provide any consideration to the donor upon transfer. Program-related investments aren’t considered jeopardizing investments.

An excise tax of 10% of the amount of the jeopardizing investment is imposed on the foundation, and a 10% excise tax is also imposed on any foundation manager who knowingly, willfully, and without reasonable cause participated in making the investment.

If the private foundation hasn’t disposed of the jeopardizing investment within the taxable period, it faces an additional excise tax of 25% of the amount involved, and foundation managers are subject to an additional excise tax of 10%.

Checklist for Next Steps

Alternative investments may make sense for many private foundations. They allow for diversification of the investment portfolio and may realize a higher rate of return for the foundation.

In looking into alternative investments, private foundations should consider the following questions and steps:

- Does the foundation have a section on alternative investments in its investment policy?

- Does the foundation’s investment policy address the manner in which alternative investments should be used in the portfolio?

- Has the foundation’s investment advisor met with the board or investment committee to educate its members on alternative investments?

- What fund structure is most appropriate for the foundation? Does the foundation want a fairly liquid investment, or could it invest in an illiquid investment?

Before investing, analyze alternative investments for tax reporting requirements:

- What are the potential tax filings and the cost of those filings?

- How will the fund communicate reporting requirements to the private foundation?

- What’s the structure of the investment—partnership, corporation, or trust?

- Is it a foreign or domestic investment?

- Will the fund generate unrelated business taxable income?

- How does any potential tax generated compare to the returns provided to the foundation?

- Are there foreign reporting requirements?

- For excess business holdings purposes, do any disqualified persons also own the investment?

We’re Here to Help

If your private foundation has any questions about the tax, fiduciary, and regulatory implications of alternative investments, please reach out to your Moss Adams professional.